The following is the reprise of a conversation between myself and my sister-in-law. Joanna resides in Portland, OR, home of Powell’s Books. I’ve transplanted to and branched out in Boston, MA, which claims the first free public library in the U.S. (Internet says: Boston’s the second behind NH. Sorry, Boston.) It’s no surprise to anyone who knows us that we’ve both engaged in book slinging. Joanna put in many years as a bookseller and, in high school, I was employed at my local library. I also once kept a blog devoted to visiting libraries.

In the past month, I completed revisions on a 60k+ word novel intended for young readers and Joanna has, on hire, proofread those very same 60k+ words back when they were more like 70k+. There’re other crossovers in our combined reading Venn diagram but, more importantly for this discussion, we represent a breadth of experiences with, in, and around the world of reading/writing/BOOKS.

Phoebe-in-Boston

Recently, I applied for an opportunity for free coaching for new and emerging writers and the application required that I list three works I’ve read, similar to my manuscript. Off to Goodreads.com I went.

Reading through my digital shelves, the first thing I noticed is in the past decade I only rarely read novels featuring characters similar to the young people in my manuscript, with the obvious exception of graphic novels.

Second, the (non-graphic) novels I read with characters age 12 or so are stylistically and topically, very, very different from my work. Contemplating this, I wondered: has there been a shift in the market? Via casual perusal, most of what I came across was: humor/boys-being-wacky or girls-being-plucky; recovering from the death of parent/custodial adult or similar emotional orphaning; earnest identity crisis, and discovering latent, magic powers. This list admittedly excludes outdoor-adventure, sports, or kiss-your-cheek romance, which I didn’t read as a pre-teen, teen, or young adult, and certainly don’t read now.

Searching online and off, I asked myself: has the market maybe shrunk? Converted into something I no longer recognize? Or perhaps I’m searching the wrong places?

The books I remember from being a 12-year-old, occasional Judy Blume-reader who was more attuned to Diana Wynne Jones and early-days Jacqueline Woodson (though I was quietly hooked on Tolkien, dry, pastoral Westerns, and true-life hospital dramas,) appear to have migrated up to YA, or otherwise flowered into a new crop of verse-books, employing poetry for the heavy lifting.

All that’s fine. Sure, things change, but who’re my novel’s play-cousins? In these days, these markets, where does my manuscript fit? Just what kind of fiction IS this?

Joanna-in-Portland

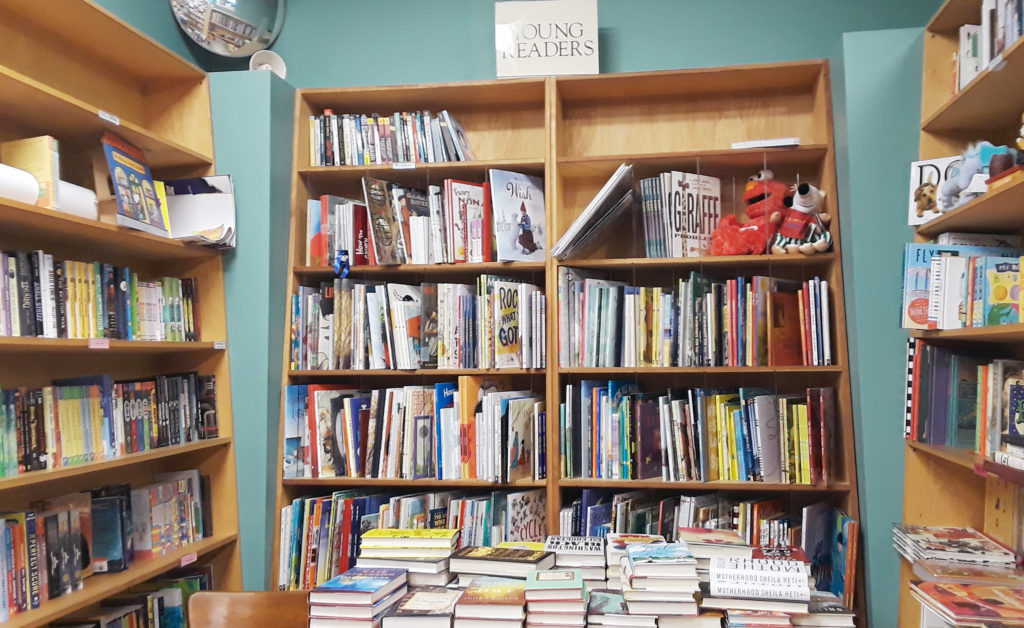

Last night I visited a small independent bookstore for a reading and found myself browsing the Young Readers section, mentally preparing for this conversation-in-writing.

I wondered, not for the first time, if book stores, especially the indie ones, are free to simply categorize their books depending on the amount of shelf space they are working with, and/or their label-making capabilities.

At the shop last night, a sign reading Young Readers was displayed high above a cozy nook lined with bookshelves and a large table piled with titles. This section included picture books as well as fairly hefty-looking middle grade books. Close by was a large (-ish) area dedicated to Young Adult novels. I pulled a couple off the shelf at random and read the blurbs on the back covers: the first expressed something along the lines of playing guitar till one’s fingers bleed to distract from the pain of unrequited love, and another featuring a young woman running across the country due to trauma in her past (the nature of the trauma remained unclear.)

What was interesting was that neither one of them read as particularly young adult to me. If Young Adult comes to mean increasingly Adult, where does a book that feels older than Middle Grade, but highlights characters who are undoubtedly young, fit in?

What kind of fiction is it?

I thought Phoebe’s manuscript was sort of similar to Judy Blume’s Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself, (which, by the way, ranges from being called “young adult”, “young readers,” or “kids” by a random sampling of three different major websites), or Just as Long as We’re Together, but with more of a boy vibe, like Fast Sam, Cool Clyde and Stuff, by Walter Dean Myers. Pre-teen characters who are faced with having to suss out bigger problems with depth beyond their years (because, life) but who are equally, if not more, focused on their friendship dynamics and school and the beginnings of romantic feelings (because, kids). A mash-up, perhaps, between the above-mentioned, plus Jacqueline Woodson and a little John Green: authors who write young characters, drenched in reality, with a clear intention and deference for their young audience, while not sacrificing the earnestness and innocence that separates these books from those actually written for adults.

Kids today are young adults in some ways before the previous generations were, in that information is accessible to them about everything they can Google with their hot little hands. They seem to look and think more like adults too. Furthermore, fashion, music, technology, etc., all cater towards the younger consumer. What defines young adulthood changes, and the literature evolves along with it. Author Michael Cart, in an article I found on Smithsonian.com, points out that it wasn’t until the mid-1940s that librarians first began calling teenagers “young adults,” and 1970 that “serious young adult literature was recognized.”

There was no category for young adult literature until American youth culture manifested itself, according to Cart. And then of course, the youths being described as “young adults” surely only represented a small portion of the population. Surely, “young adults” are now worlds away from what they were when that term was coined; shouldn’t the categorization evolve as well? Also, since young adult literature and adult literature are often meant to blend or “crossover” as many titles do today, shouldn’t there be as many literary subsections for the younger population as well?

Finally, how useful are these classifications anyway? Certainly they are necessary when it comes down to just plain organization. The difference between bookstores and libraries involves making books sell-able to the right market versus making books available to the right audience. Obviously both are important when you are trying to get your book published, but shouldn’t an author have some say in where their creation ends up?

The truth is, in my experience as a bookseller, not to mention my experience of being a young person–kids are gonna read what they wanna read, no matter what label you put on it. But what do they want? I think they want what most of us want: to be taken seriously, not be talked down to, to be entertained, and to have options. Some kids want sci-fi/fantasy, some want romance, some want poetry, some want to read about coming of age in a bleak, dystopian distant future and many want to read about kids living in a town or school that could be their own, with characters they could see themselves hanging out with.

By the way, they want what they can’t relate to, too! For example, I couldn’t have a horse, but didn’t I long for one? So I devoured books about horses and the kids who were lucky enough to be around them. And for some reason there was an abundance of books available to me about girls with debilitating disease, so I read them as well. My dad urged me to try Don Quixote, which I rejected because I wanted to read the 1,842nd installment of The Baby-Sitter’s Club.

Phoebe-in-Boston

Phoebe-in-Boston

I totally hear Joanna about those horse books.

I fell into them as well. They were fun. They were plentiful, which speaks to the importance of what’s available. Dozens of ponies trotting around a Virginian island whose name I still can’t quite pronounce, sure! As a kid I read those stories ‘til the cows (horses) came home but books featuring African American or Asian American or Latinx or Indigenous and First Nations kids that were not also bittersweet encapsulations of The Desperate, Dignified Struggle, much less so.

It might seem as though this blog post is a #representationmatters sneak-attack but, in truth, the two ideas intersect. Whatever the myriad pressures on publishers, booksellers, and libraries to buy narrative works and get them into the hands of their intended audiences, a similar weight bows the shoulders and hearts of writers like myself because, on one hand, I represent risk related to my color and gender, and the other, my work could be seen as a whole different risk – a conventional-market misfit.

What kind of fiction IS it, I can’t for sure say. Nowadays, I tell folks: my protagonist is 12-years-old and I let conversations spool out from there, as unique, meandering, and curious as kid-me wandering the library stacks with my fingertips bump-bump-bumping along book spines.

THANKS

Gracias especiales to my good-buddy-sister Joanna: poet/crafter/thinker/reader/explorer. You can find her online at: https://dreamyscrape.wordpress.com/

– Phoebe Sinclair, 2018 WROB Ivan Gold Fellow