Some writer’s math:

The protagonist of my novel manuscript, Jonas Adams Abraham, is 12 going on 13. The manuscript itself is 12. When I started writing Jonas’s story, I was 26.

Liaa, the 15-year-old protagonist of a manuscript I put to bed in order to focus on a potentially more commercially viable book (see above) can be counted, in effort-years, as 7. I conceived of the novel while I was an undergrad at Emerson College, probably age 19.

A short graphic story featuring a 11-year-old (and later her 15 and 17-year-old selves) is approximately 7 years into endless-tiny-revisions. 3 or 4 years younger than Jonas in terms of sequence, the script represents hours rather than years of effort.

Other writing has similarly aged, as I have aged, moving further and further from our society’s specter of the overnight (and enviably young) author-sensation. As I stretch into my fourth decade of being an animal on this beautiful, awful, bizarre, heart-breaking planet, my gift of experience and dreams for what-might-be enter with me.

Together we are growing up.

[/end math!]

I attended a lecture by Pulitzer Prize winning author Junot Diaz where he described himself as a slow writer. In my memory of his self-depreciating story, Junot painted his peers as writing circles around him —his works requiring long years of incubation while theirs stacked like shiny red apples at a city grocer. It was the first time I’d heard a published author describe this phenomenon and the truth hit me with a spine-straightening zap of static electricity. I took notice.

I tried that idea on: slow writer.

Some pondering:

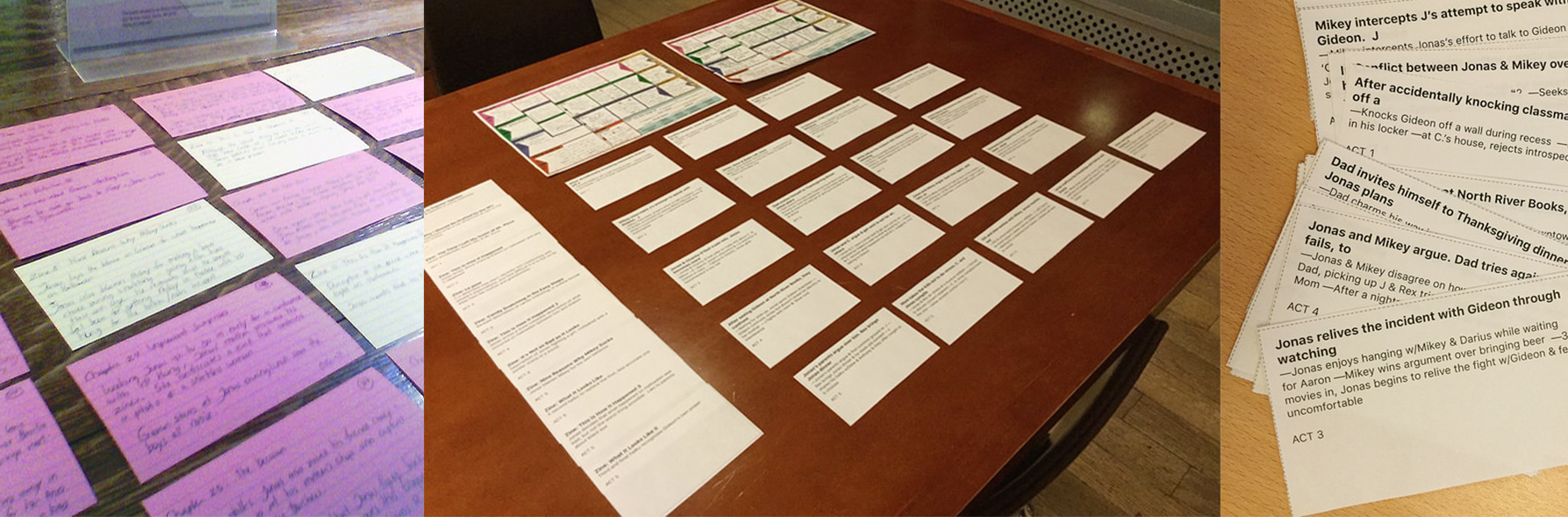

Slow writing. Manuscripts that catch up to and then out-age the characters who roam their pages. Words with enough history to manifest their own internal humor—self-referencing for the benefit of no one in particular (beyond the author.)

What does it mean to be slow now, when fast is culturally mandated? I pose this question while typing on a tiny, high speed iPod keypad, this mini computer that I slip into my pocket as I zip across a major city in our nation of nations —where many cultures move together at different paces, generally not peaceably.

I write this understanding that time is a construct by which my body must abide. But time doesn’t truly exist in my manuscripts. And the manuscripts exist without relation to time. They are or they are not. On my good days, I do not blame my works for being what they are. I can neither stop them nor speed them up. Nothing I do has much impact except for my resolve to arrive again and again, twirling time fluffily onto a white paper cone, or maybe creating an elastic loop as I build on ideas and cultivate the gifts of my characters’ laughter and heartbreak, their triumphs, mistakes, and revelations.

It seems this could go on forever, but it won’t because I cannot. My physical self is limited in a way art will never be. Really, which one of us is slow? Which of us just is?

[/end pondering!]

Pretty words, huh? Existential thoughts even as I, in the more practical sense, park my butt on a chair, or stand leaning over a laptop, and plant a hand on the keyboard, typing in that curious one-handed way I do where the craft spools out —my right hand magically comporting itself through the middle-school-taught positions, keyboard-left and keyboard-right, without having to peek. Slow going. Real slow.

Real and slow.

-Phoebe Sinclair, 2018 WROB Ivan Gold Fellow