Lately, I’ve been questioning the use of the second person point of view in fiction. The you pronoun features prominently in my collection, but as I work on what I hope will be the manuscript’s final story, I’m finding myself overly conscious about choosing you over I or he. I keep stopping to ask, “Is this POV earned?”

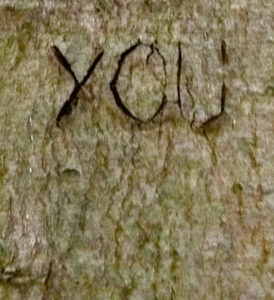

I’ve long resisted the idea that using the second person requires more justification than other narrative strategies. If I interrogate my choice to use you over I, I’ll admit that on some level, it just feels more natural. When I wake for work after a late night of writing (or Netflix binging), and I glance sleepy-eyed into my bathroom mirror, I don’t say to myself, “I look like shit.” I say, “You look like shit.”

And I know exactly to whom I am speaking.

When I read novels written in the first-person—novels that haven’t troubled themselves with an invented occasion for my reading them—I sometimes wonder of the narrator, To whom is this story being told? What assumptions have the narrator made about the recipient of this story?

With third-person narrators, I might wonder, Who is telling me this? Is that you, God?

In second person narration, when you stands in for I—that is, when readers or secondary characters aren’t being addressed—we understand that our protagonist is both narrator and narratee; we are privy to a telling or retelling of a story handed off to, and received by, a psyche fractured by the passage of time and/ or an altered understanding of events. This fracture, I would argue, more similarly reflects how we experience the world: Subject meets stimuli and interprets then reinterprets to create narrative; we tell ourselves the story of what is happening to us as it is happening, and many times afterward. Similarly, our second person protagonist exists both within the story’s events and in the consciousness that orders and reorders the events to create meaning.

In second person narration, when you stands in for I—that is, when readers or secondary characters aren’t being addressed—we understand that our protagonist is both narrator and narratee; we are privy to a telling or retelling of a story handed off to, and received by, a psyche fractured by the passage of time and/ or an altered understanding of events. This fracture, I would argue, more similarly reflects how we experience the world: Subject meets stimuli and interprets then reinterprets to create narrative; we tell ourselves the story of what is happening to us as it is happening, and many times afterward. Similarly, our second person protagonist exists both within the story’s events and in the consciousness that orders and reorders the events to create meaning.

For those of us who exist outside of the dominant culture, this experience of psychic fracture is particularly salient. As a person of color and a first-generation American, I am tasked with mastering my own cultural references and white America’s. To succeed within the larger culture, to some extent, I must cultivate a dual consciousness that often sets me at odds with myself, as I view myself through the lens of the other. The second person POV uniquely allows a character reflection through the lens of a removed self, the distance created by you implying a second consciousness.

Perhaps third person feels too authoritative to me right now because my reality is constantly in flux. Perhaps first suggests singularity, and even in the plural gestures to a cohesion that I just can’t identify with. Because, even now, the voice in the back of my head is telling me, “Shut up and write your story.”

-Jonathan Escoffery, 2017 WROB Ivan Gold Fellow