I’ve been a newspaper reporter, a public relations guy, a technology marketer, a salesman, an entrepreneur. I failed at most of that, though I wasn’t as terrible a journalist as I was at selling things, and when my cash flow tightened, I could always eke out a living behind the wheel of a Boston yellow cab (a skill I learned from a guy by the name of - no kidding! - Pizza Mike).

But until I started writing memoir, about as self-centered an endeavor one could consider, my ability to work rarely depended on my emotional state. Lately the question I keep revisiting is this: How do you write when your world is falling apart? How do we create amidst the chaos?

Steven Pressfield offers a hard-ass, football coach kind of answer: You’re a professional. Get your ass in the chair. “We show up no matter what,” he says in The War of Art. “In sickness and in health, come hell or high water, we stagger into the factory. We might do it only so as not to let down our co-workers, or for other, less noble reasons. But we do it. We show up no matter what.”

That’s all well and good. But sometimes the ‘no matter what’ is beyond overwhelming. It’s more than a presidential election that doesn’t go your way, or an attack by that newly elected president on beliefs you hold most dear. Sometimes it’s turmoil closer to home, a personal crisis that rocks your existence, shifting the very ground beneath your feet. Daily assumptions are suddenly not quite so. It’s amidst this kind of disruption that I lose my voice. Words fail me, and it’s easier to immerse myself in foolish distraction — web surfing, sports or television — than it is to focus on my keyboard.

Frankly, I always found words easy to come by when drafting ten column inches of news on the latest protest at the local nude beach, or a press release on my client’s latest product launch. Even marketing copy for the courier company I once owned would roll off my keyboard in the midst of plummeting financials. I couldn’t sell, but boy could I write a brochure. But when the words are personal and the havoc’s hitting home, writing can be the hardest thing to do.

It takes a writer like Mary Karr to pull me out of my slump. She writes, with characteristic whit in The Art of Memoir, “I once heard Don DeLillo quip that a fiction writer starts with meaning and manufactures event to represent it; a memoirist starts with events, then derives meaning from them.” That I get. I’ve been mining tumultuous decades of my own for close to 300 pages now. The thing is, meaning can take time. And time can mean NOT writing, at least for a little while. And that’s okay. Sometimes we need to regroup.

The Zen master Thich Nhat Hahn, in his most famous short book, Being Peace, offers a short poem he uses help find his center at the beginning of his daily meditations:

Breathing in I calm my body.

Breathing out I smile.

Now, I’m no Buddhist monk, and I don’t meditate anywhere except perhaps the keyboard. But maybe the guy has a point. Maybe a short mantra is the way to navigate the space between life and writing:

Breathing in I consider my letters.

Breathing out I type.

Umm. Yeah. No. Better to live with the drama and anxiety. That’s where the real stories lie.

--

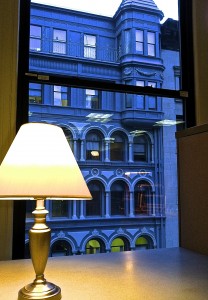

On a brief personal a note, this is my last blog post as a Fellow at the Writers’ Room. I was shocked when Debka emailed me a year ago with the news: you’ve been chosen, she wrote. The Room would like to offer you a Fellowship. It was a privilege to have been given the time to work and to think of myself solely as a ‘writer.’ I’m grateful. I offer thanks to the Board and to all the other members. I’m excited to stay on at the Room, and to continue writing and sharing my work in this vibrant community. For the foreseeable future I’ll still be writing at my favorite desk near the State Street window, and I’ll still have my hammer and nails at the ready. Please let me know what needs fixing.

On a brief personal a note, this is my last blog post as a Fellow at the Writers’ Room. I was shocked when Debka emailed me a year ago with the news: you’ve been chosen, she wrote. The Room would like to offer you a Fellowship. It was a privilege to have been given the time to work and to think of myself solely as a ‘writer.’ I’m grateful. I offer thanks to the Board and to all the other members. I’m excited to stay on at the Room, and to continue writing and sharing my work in this vibrant community. For the foreseeable future I’ll still be writing at my favorite desk near the State Street window, and I’ll still have my hammer and nails at the ready. Please let me know what needs fixing.

-Mike Sinert, 2016 Nonfiction Fellow