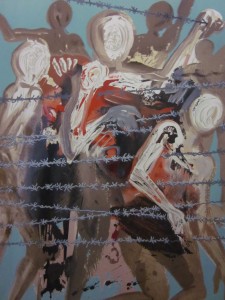

Years ago it occurred to me that all my life there has been a war somewhere on the planet. Whether a big war or a “brushfire” one or a “conflict,” always somewhere people were being injured and killed, people being displaced, their homes destroyed. People in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, North Korea and South Korea, Lao and Hmong, Serb and Croat, Arab and Israeli . . . it goes on and on, war or wars in period after period, this or that country, and always the dead, the refugees, and the exiles war makes.

When I was somewhere between infancy and three years of age, my older brother and I spent weekends with our father’s parents in Queens, New York. Weekends there meant Sabbath observance from sunset on Friday until sundown on Saturday. In the afternoon, after our grandfather returned from shul and our grandmother (my grandfather’s second wife, my father’s mother having died in 1918, in the ’flu pandemic, when he was eight years old) had served lunch, children were sent to nap, my brother in one room of the apartment, I in another.

The room in which I was to sleep was our young aunts’ bedroom (where they went on weekends when we visited, I never learned). Along one long wall there was a bed at each end, and along the other at each end there was a vanity and its small chair. Above the headboard of one bed hung Gainsborough’s “Blue Boy,” above the other, Thomas Lawrence’s painting of a young woman called “Pinkie,” though I did not then know the names of the pictures or the artists, nor why those paintings were there, seemingly forever.

There were other pictures in the room, photographs wedged into the frame of the mirror over the vanity close to the door to the bedroom and therefore far from the bed where I lay. Often on Sabbath afternoons, while I should have been asleep, my grandmother quietly entered the room. If I were not sleeping I’d have shut my eyes, to fool her. She sat down in the small chair of the far vanity, her elbows on the top of the vanity, her hands together under her chin, and stared at the photographs. I watched her face in the mirror. Soon, she took the photographs down and thumbed through them, slowly, stopping longer with one or another, soundless as tears fell down her cheeks. I remember wondering who the faces were and why she cried, but I knew, as children do, not to ask, and not to let her know that I watched her. Whether I told my brother what I saw, I can’t remember, though I saw it time and again.

Later, I learned the photographs were of of relatives, mainly hers, sent to her from Russia, and some were of relatives of my grandfather, all of them people who had stayed behind, perhaps changing their minds too late. Eventually the family learned almost all of them died in the camps, of disease or killed. One grew up Jewish absorbing such knowledge then, though not every family talked about it. The photographs disappeared from the mirror; I must have noticed that on a visit. Maybe my grandmother told me whose faces those were and who they had been when I was in high school, studying European history, which briefly included the Holocaust.

My father had known some of those people. As a young surgeon, he’d had a fellowship for 1936-1937 to work for half a year at a London hospital and half a year at a hospital in Berlin. Before starting the fellowship, he traveled to Russia and Poland—national borders in such contested areas being unstable in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish and non-Jewish communities might be said to have moved from one country to another while staying put, sort of like trench warfare. In London, the “senior” in charge of my father’s work was openly anti-Semitic. When, at the end of the first half year my father went to Germany, on his first day at the hospital in Berlin he was questioned about his accent in German (clearly recognized as Yiddish-tainted) and taken on a tour of the hospital, including the Jew ward. Within days, he was back in London, where he expressed to his senior a strong wish to spend the second half of the fellowship year there, a wish that, almost unexpectedly, was granted.

As a front-line Army surgeon, my father entered Europe in a duck boat as part of the Normandy invasion. For the rest of his life a calendar of the war lived in him: June was Omaha Beach, December the Battle of the Bulge, April Buchenwald. Every December he was overcome by cold, the record freezing temperatures, the snow, mud, ice, and frostbite of 1944. When the Army was forced to retreat, my father volunteered to stay with the American wounded too ill to be evacuated, for which he later was awarded a bronze star. When the Germans arrived, he was captured, and the Colonel in command ordered him to care not only for his Americans but also for wounded German soldiers. Once the Americans were well enough to withstand removal to a prison camp, my father, blond, blue-eyed, built like the wrestler he’d been in college, and able to speak German, however tainted by Yiddish, escaped. In April he was with the Army for the liberation of Buchenwald. He never forgot what he saw. He took photographs for the medical records and made copies for himself, which he showed to me when I was in high school, studying history. For three weeks I could not sleep through the night. I was fourteen.

Having been raised on one war and then old enough during the Korean “conflict” to read newspapers, which puzzled me by the constant mention of parallel lines, it may be no surprise that I became interested in war and, later, war poetry, coming upon, for example, Joel Barlow’s “Advice to a Raven in Russia,” written when Barlow, sent to Russia in 1812 on behalf of the U.S. government to meet with Napoleon, witnessed the devastation wrought by the failed attempt of the Grande Armée to take Moscow. From World War I, the “Great War,” there are, in English, the British poets, those of 1914 and 1915, such as Rupert Brooke and Julian Grenfell, for whom heroism and glory were inherent in war, and others later, such as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, living and dying, as Owen did, in the fruitless repeated battles of trench warfare, seeing and writing about those at the front, the wounded, the crazed, the dead, and about the generals, at the rear. They wrote, too, about soldiers on leave, in “Blighty,” unable to face or talk about the war with mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters, many of whom continued to praise what the soldiers fighting in it, witnessing it, protested in poetry and in fiction, such as Frederic Manning’s Her Privates We (1930), the title taken from Shakespeare, so the pun is easily guessed. An astonishing poem written early in the war is by Charles Hamilton Sorley, now almost unheard of, a twenty-year-old soldier killed on the Western Front in May of 1915:

When you see millions of the mouthless dead Across your dreams in pale battalions go, Say not soft things as other men have said, That you’ll remember. For you need not so. Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know It is not curses heaped on each gashed head? Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow. Nor honour. It is easy to be dead. Say only this, “They are dead.” Then add thereto, “Yet many a better one has died before.” Then, scanning all the o’ercrowded mass, should you Perceive one face that you loved heretofore, It is a spook. None wears the face you knew. Great death has made all his for evermore.The Vietnam war, in Vietnam called the American war, has a literature of its own: stories such as Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried (1990), and poetry by such poets as Kevin Bowen, Bruce Weigl, and Fred Marchant, a Marine who, while serving, filed for and was awarded conscientious objector status. Of necessity, I skip much: there are now many anthologies of war poetry, and poetry is being written in other languages where war is now going on.

But an interest in war may not be unique to me, it may, rather, be ordinary, given the world we live in. An interest in poetry of war, poetry against war, poetry telling of the effects of war, written by combatants, former combatants, and noncombatants, men as well as women, such as the poets and translators Martha Collins and Eavan Boland, may well be increasingly of interest, given the world we live in.

-Ellin Sarot, Gish Jen Fellow for Emerging Writers